Carrigan Head LOP 71

For six long years, they were the nation's official 'vigilantes' keeping a 24/7 lonely vigil on Éire's Ireland's Eyes and Ears of WWll. The coastwatching service was established the week the Second World War Éire's 'Emergency' - broke out in September 1939.

At first amalgamated with the Marine Service, each became a separate entity on 1 July 1942. Originally only equipped with two-man 'bivvy' tents, after several of them were blown into the sea from their exposed locations, simple, concrete pre-fabricated structures known as 'Look Out Posts' (LOPs) were provided, with LOP 71 situated at Carrigan Head on Sliabh Liag while to the left at St Johns Point you had LOP 70 and to your right in Glencolmcille you had Rossan Point which was LOP 72. Article by the late Joe Gallagher about the local LOPs HERE.

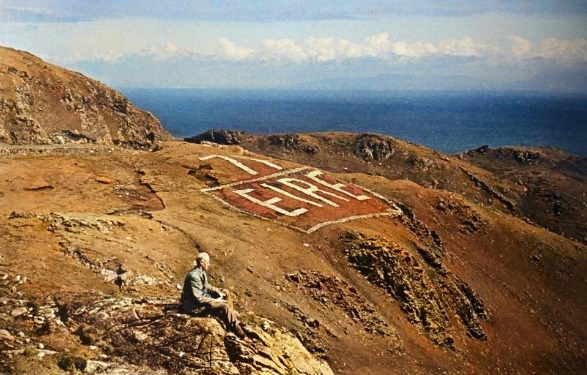

My grandfather at Carrigan Head in the 1940s

Measuring just 9ft x 7ft with sea-facing bay windows, the huts were totally devoid of creature comforts; the only exception being a small stove provided for heating and cooking purposes.

Each hut was equipped with a telephone, telescope, binoculars, Admiralty charts, a fixed compass card, semaphore and international code flags, a Morse lamp, first-aid kit, handbooks for identifying belligerent aircraft and warships, and bicycles.

The huts were numbered clockwise around the coast from Carlingford Lough to Lough Foyle, many in remote, and indeed hazardous areas. Lamb's Head (LOP 33, still extant) on the Ring of Kerry being a good example of the latter; in stark contrast was LOP 6 (demolished) at Howth Head, Co. Dublin, which was but a hop, step and jump from the nearest hostelry!

By war's end there were eighty-eight LOPs placed at strategic points along the fire coastline, positioned on average every five ten miles apart.

The volunteer soldiers who manned them were responsible for monitoring any sign of belligerent activity on sea or in the air, and to warn of the first sign of an invader.

They took their duties very seriously and anything untoward that came to their notice was diligently entered in the official log book, about 500 of which have survived and are deposited in Military Archives and available to read on-line, you can read the Carrigan Head on HERE.

Additionally, a telephone message was instantly transmitted up the chain of command with full details of the occurrence.

The force was organized in eighteen districts. Each district had a District Officer (holding the rank of 2nd Lieut), a Sub-Officer and a Quartermaster whose ranks varied depending on the size of the district. Each district had between three and eight LOPs, each post having a Corporal and seven Volunteers.

The Volunteers were unpaid (save for a small subsistence allowance of 3/6d a day) and unarmed, many coming from the Volunteer Force which meant they continued to wear this distinctive uniform for some time even after the cadre was absorbed into the new Local Defence Force (LDF). Each Volunteer was required to live not more than six miles from his designated LOP. The establishment of the force numbered some 750, all ranks.

Every LOP was issued with the official Handbook on the identification of Aircraft, example HERE.

Volunteers invariably came from the local coastal community; men and youths whose knowledge of every nook and cranny of the seashore, and every nuance of the tide, would prove all-important in the tasks they were asked to perform.

Affectionately known by the rest of the defence forces as the "Saygulls' (seagulls), like their avian namesakes they were to be found, night and day, perched in the most precarious places on cliffs all along the coast, constantly scanning the horizon.

Each two-man team worked shifts of eight or twelve hours, in two-hour stints; one Volunteer patrolling outside in hail, rain or shine, while the other manned the telephone.

From early 1943 large letters, each thirty feet in height, spelling out the word 'ÉIRE' were painted in a prominent location next to each LOP, accompanied by the LOP identity number.

Ostensibly to warn all belligerents that they were encroaching upon Irish airspace, the scheme had been initiated at the request of the US authorities: each Allied aircraft carried a chart corresponding to the numbers of all the Irish LOPs and their positions.

Overflights had increased from 700 in 1942 to some 21,000 by 1944, resulting from the basic navigation equipment on contemporary aircraft making long flights over water. In recent years, the Éire Marking Project has uncovered at least thirty of these signs and restored many.

According to one historian '...the service was deemed one of the more effective branches...supplying vital information as to the movements of ships and aircraft in Irish territorial waters, informing GHQ of any attacks which occurred within those waters and reporting the location of mines which had drifted free of their moorings.

As is now known, G2 (Irish Military Intelligence) constantly shared any relevant information with the British Admiralty and M16.

The occupants of many lifeboats grievously wounded and in terrible distress, survivors of attacks on convoys and sea battles, frequently came ashore near one or other of the LOPs where they would be assisted and comforted by the Volunteers on duty who rapidly summoned the emergency services.

Drifting sea mines posed a grave threat to life and limb ashore. Designed to sink the largest merchant ship with which they came in contact, one can only imagine the devastation wrought if exploded on a beach full of people.

One such incident occurred at Ballymanus Strand in Co. Donegal in 1943 when the local District Officer arrived on his motorcycle to find a large crowd in close proximity to a magnetic sea-mine. Before he could safely evacuate the entire area, the device exploded, resulting in, tragically a death toll of nineteen young men and boys.

Not all flotsam and jetsam was unwelcome. The LOP at Sligo alone salvaged some 500 tons of badly-needed rubber, carried as deck-cargo by Allied shipping. In the event of a convoy being attacked, the bales of rubber invariably were the first things to be jettisoned, many finding their way to our shores. Presently, the raw rubber would be transported to the Irish Dunlop Rubber plant at Centre Park Road, Cork, to be transformed into badly-needed tyres for the Defence forces and emergency services, and other essential commodities. By 1942, the supply of rubber by conventional means had all but dried up.

One fine summer's day in 1940 Rosslare Port in Co Wexford came dangerously close to being blown up due to the vigilance of the Coastwatchers at Greenore Point LOP. The Volunteer on outside duty, scanning the horizon with his binoculars, could hardly believe his eyes when, suddenly, the whole sea seemed to be teeming with ships - all heading straight for the Irish coast.

An urgent telephone message was transmitted, and Army Ordnance engineers were quickly despatched to Rosslare where explosives were already in place, waiting to be primed if the day of reckoning should ever come. At the last minute the fleet changed course and steamed off, away from Ireland.

As noted, some 500 Coastwatching Service log books are deposited in Military Archives, Dublin. All provide a true and accurate account of the activities of the service during the war years, unaltered and uncorrected in any way. You can view them online HERE.

*Text from "The Saygulls" Irelands Eyes and Ears of WWII by Pat Poland, published in "Irelands Own" Oct 17 2025

*LOP 70 Information can be found HERE

*LOP 72 Information can be found HERE